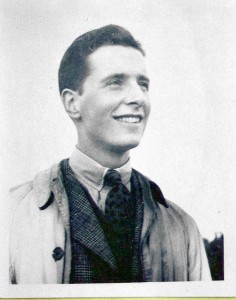

William Robert Smith, D.F.C.

July 12, 1922 – February 25, 1944.

At 9:15 on the evening of February 25th, 1944 a Lancaster II bomber, “F for Fox”, (DS791) took off from RCAF Squadron 408 at Ouse-on-Linton, Yorkshire. Aboard was a crew of seven: Flight Lieutenant Bob “Willie” Smith (pilot); Flying Officer Cy Ridgers (navigator); Flight Sergeant Lloyd “Red” Beer (bomb aimer); Flight Sergeant Donald “Ginger” Bowler (air gunner); Flight Sergeant Clarence “Butch” Draper (air gunner); Flight Sergeant Doug Mullock (air gunner) and Sergeant Fred Crofts (flight engineer). Their mission was to drop an 8,000 pound bomb and incendiaries on the south German city of Augsburg. On completion the crew was promised leave – for Bob Smith, an anticipated month-long trip home, then a posting to an instructional station where he would train aircrew while flying Spitfires.

This was an experienced crew, the most senior on the base. All were in excellent spirits, and the trip out was uneventful. The flight plan called for them to release their ordnance, then continue flying on a northerly course for five minutes. They then turned south-west in preparation for the trip home. It was at this point, near 1:00 a.m. that they were attacked by a ME 110 that released several canon shells from beneath their unprotected belly, a blind spot. The port engine and wing was hit, though the ensuing fire was flooded with the automatic fire extinguisher. Bob put the plane into a dive, from 30,000 feet to about 19,000, to fully extinguish the flames. But mid-air gunner Doug Mullock noticed a second fire that could not be extinguished, and the crew prepared to bail out. Because he had the furthest to travel, Doug prepared first. “Red” Beer set about to assist Bob and Cy into their parachutes. At this point, navigator Cy Ridgers reported that his table (set mid-plane) was on fire. Bob calmly suggested that “We’d better get a move on, then.” All movements were methodical, as had been rehearsed, and no-one panicked. Bob turned the plane on its side to avoid further hits, but the Augsburg anti-aircraft battery fired “directive” flak – essentially a radar-guided flak that became deadly once it was “locked in”.

With the plane almost on its side it was difficult to move towards the escape hatches. The rear hatch seemed stuck as the plane went into a spin… and exploded. Doug Mullock was blown free and briefly knocked out. When he came to he was floating in the air, and reflexively yanked his parachute, landing in three feet of snow near the town of Seeburg, about twenty-eight miles south-east of Stuttgart. The others died instantly and were thrown free of the plane. Pilot and crew leader Bob Smith was only twenty-two years old.Mullock was captured within twenty-four hours near the town of Reitheim and became a prisoner of war. After his release in May of 1945 he confirmed that the plane indeed had been shot down.

Bob’s C.O. wrote to his parents:

“We lost one of our best aircrews when this aircraft did not return, for it had already been mapped out for a great future with my squadron. Your son [Bob] had 28 operational

trips to his credit and a total of 186 operational hours over enemy territory, and he was one of our “Ace” pilots.” (06.03.44)

Bob’s parents were informed within two days of his disappearance, identifying him as “missing”. A letter to the Smiths from P.O.W. Doug Mullock, dated May 1, 1944, and delivered by the Red Cross provided details of the last flight. By October 1944 he was presumed dead, and officially declared dead on January 10, 1945. This was communicated to the Smiths by March 1, 1945, but his mother continued to believe him alive as late as April 25, 1945 – perhaps the most difficult aspect of the war at home.

After the war the Missing Research and Enquiry Unit (M.R. & E.U.) or the Missing and Research Enquiry Service (MRES) provided some of the final details, including the recovery of the bodies and their interment. They have been buried in the DurnbachBritishMilitaryCemetery in multiple graves (Row “E”, Nos. 8-11, Plot 4) in Bad Tolz, Germany.

Early Training

Bob enlisted in Toronto on July 22, 1941, ten days after his 19th birthday. He was immediately instated and given leave until September 9, 1941. It appears that many from North Toronto Collegiate Institute enlisted at the same time, and he mentions them frequently in his letters. He is overjoyed when he meets up with high school friends Jack Willmot and Ed Baillie in England.

During high school Bob was active in sports, including skiing, swimming, table tennis and hockey. As a student he worked two summers as a clerk, and completed first year studies at VictoriaCollege, University of Toronto, with particular interest in political science. With his exceptional curiosity and writing skills he might have become an academic. He stood 6’ and weighed 167 pounds in 1941. His blood pressure measured 110/76. By November of 1942, just before embarkation, he weighed 182 lbs with a blood pressure of 105/70. During his training in Canada he spent a week in hospital with “acute naso-pharyngitis”, but was otherwise “fit for overseas duty” (22.10.42). Concerns about his eyesight came close to preventing him from flying, but his Manning Station examiner declared him “responsible”, with “serious intelligence” and “average emotional stability.”

#3 Training Camp, Mont Joli, Quebec. (October 27, 1941 – February 2, 1942)

Bob was part of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan in which Canada agreed to train pilots for the war effort in Europe. Eager teenagers came to Canada from Australia, New Zealand, England and the United States to learn their craft. But seventy percent of the candidates were Canadian boys. The first camps to train airmen were built right across the country, adding to the two RCAF camps at Trenton and CampBorden. One such facility was #3 Training Camp at Mont Joli, Quebec (near Rimouski) where bulldozers and graders tortured the terrain until it looked like No Man’s Land. Cooks had no kitchens, MO’s had no dispensaries, latrines had no toilets and “there were no lights or running water”. In such conditions Bob spent his first few months as a guard while the camp was constructed. (27.10.41 – 02.02.42)

Bob’s records indicate that he was disciplined on several occasions, first on 19.01.42 at Mont Joli. These incidents often had him “C.B.” (confined to barracks) and were the results of confrontations with ranking officers. He did not trouble to keep them from his parents, though his letters are devoid of a description of the offences.

At Mont Joli he learns military discipline, and begins to work long hours. While the camp is under construction (no running water or plumbing – 01.11.41) he has plenty of time to eat, sleep, play snooker and write letters. He makes friends easily, though seems most attached to former N.T.C.I. chums. His ability to speak French enables him to make friends in the village of 3000, though the locals as a rule are unwelcoming of the recruits. He takes the time to canvas various Quebecois regarding conscription, and expresses opinions to his father about W.L.M. King and the upcoming elections.

As the camp nears completion, he is assigned guard duty regularly, often throughout the night in the cold of winter, protecting the camp from intruders (saboteurs). On 05.11.41 he complains that he is now standing guard “ twelve hours a day”, with “much less time for snooker.”

But in general Bob’s letters from #3 ETC (Elementary Training Camp) Mont Joli are newsy-folksy missives with frequent reminders of friends from home and anecdotal descriptions of social evenings – his attempts to grow a moustache, his assigned nickname of “Fruity”, (due to the numerous packages of canned fruit sent from home and shared with his mates), his excitement that Glenn Miller is coming to Toronto, his regular attendance at mass in Mont Joli, reference to a train wreck that affected many in town, and an on-going discussion with his father on the relative merits of George Gershwin and Glenn Miller. He attends midnight mass at Christmas and promises his mother that he will not drink “too much”.

On the matter of cigarettes and alcohol, it is very clear that his mother expects him to abstain. He seems quite happy to do so, and being a non-smoker is able to exchange his cigarettes for food. Reading between the lines, his morality is an on-going issue close his mother’s heart. He has sufficient leisure to send off letters home every second or third day, and probably many more to friends and “Ruthie” that we’ll never see.

#3 Initial Training School, Victoriaville, Quebec. (February 2, 1942 – April 11, 1942)

At Victoriaville (“… reminds me of Brampton..” – 10.2.42) Bob is engaged in formal classroom lectures up to 12 hours per day. There is less of the “summer camp” feeling to his letters, and he now begins to write about the prospect of flying. His crew of “C flight” fight a constant battle with their sergeant who upbraids them for their “sloppy behaviour.” As much as he dislikes the man, Bob recognizes that the sergeant is correct in his assessment. “C flight” is constantly C.B. for poor discipline.

His studies include aircraft recognition, airmanship, engines, theory of flight, navigation, signals, math and drill (marching). He writes and passes exams with high marks, as do many in his flight. Is this due to their natural ability, or is the despised sergeant having an impact on their growing maturity? Apparently the flight had been encouraged to study together – rather than compete – to establish an esprit de corps.

All the late-night studying has affected his health, however, and he is hospitalized for a week with nasal-phrenyngitis. He is constipated and suffers an outbreak of acne, which he blames on the food and his inactivity in hospital. Within a week of his release the whole flight is quarantined with an outbreak of scarlet fever. With a crew of over 20 young men confined to a single building for ten days it is inevitable that discipline should suffer.

Bob’s eyesight weakness now manifests itself as the result of many late nights, and he is re-classified as a “pilot observer”. He is advised to wear “polaroids” (sunglasses).

During the two-month schooling Bob continues to write every second or third day, though the letters are shorter. He keeps a running tab of letters owed to various distant relatives and package donors. It is significant that he now begins to write about friends in “C flight” as much as those from home. The content is more about learning to be a soldier and his interest in flying.

By the end of the course he has placed 9th in a class of 59. Despite earlier concerns about his eyesight, he is recommended for training as a pilot. He is described as being “… neat, mature, intelligent, alert and pleasant.”

#14 Elementary Flight Training School, Portage La Prairie, Manitoba (April 13, 1942 – July 3, 1942)

It is here that Bob begins his flight training, flying Tiger Moth bi-planes and Anson Tigers. These are canvas-covered remnants from the 20’s and 30’s that are light in weight and power. In the BCATP agreement between Canada and Britain, the latter had promised to provide Canadians with more modern aircraft, but found that Canadian and British mechanical specifications did not match. Screws were threaded differently, for example. In the early years the RCAF had to depend on American and Canadian-made machines.

Again his letters are full of anecdotal detail, but with frequent references to his flying experiences. On April 23 he reports a conversation with an RAF flyer who claims that his first experience of a prairie winter was “… like walking into a stone wall.” News of the flight includes their adoption of a black Scottish terrier named “Washout”; of his bunkmate John “Springtime” Somers, a poet from Connecticut whom he refers to as a “queer” (with no tone of condescension) and with whom he “… clashed about Steinbeck and Hemingway.” He is slowly adopting an English accent (including “cuss words”) and flyer slang. His pay has been increased from $39 to $66 per month.

As for news of Toronto friends and family, he passes on congratulations to Jack Willmot on his pending engagement and refers to the “Junkin clan re-union”. He meets his father in Winnipeg while on a 48-hour pass sometime in May or June. And he makes reference to “…an invitation to dinner from a switchboard girl who put through a call to Toronto” for him. He declines, pleading the necessity to study for exams, but seems flattered to have been asked.

As for his flying, he continues to train in Moths and Ansons, frequently flies at night, and endures hours in the “Link Trainer”, an early form of flight simulator. These flights feed his enthusiasm for flying, and he begins to develop a desire to fly twin-engine craft rather than fighters. Some of his flying is daytime, some at night. He is clearly anxious to begin solo-ing, but is delayed by the weather, his average ability and difficulty in landing his craft. But he persists because he has fallen in love with flying.

In a letter dated 25.06.42 he writes…

“This morning was as gorgeous a morning as I’ve ever seen. The ground mist, when viewed from above, might be drifts of fine snow. The Assiniboine, over which it lay for a fair length of time, seemed to be frozen. Together with the neat, planned look of the farm buildings, the fields of mustard (yellow), light green and black, the regions of woodland and slough, the entire effect was overpoweringly beautiful. Above and, at times, around me, rested billowy cumulus clouds, strangely accompanied by much appreciated smooth air. I can’t hope to put into words the feeling that goes with being aloft on a day like this. Your heart flies up and you go chasing after it.”

Bob graduates from EFTS with an “A” for piloting ability, though “… he still has a little difficulty with landing”. He was ..”inclined to be nervous, but should overcome this with experience”. Nevertheless, he placed first in his class of 27, and “… possesses leadership ability with a well-balanced personality.”

#10 Secondary Flight Training School (SFTS), Dauphin, Manitoba. (July 4 – October 24, 1942)

Bob’s first week at SFTS finds him in detention for arriving back to base 18 hours late after a leave. His new station is 3.5 miles south of Dauphin and includes 1700 airmen and 200 WAAF’s. The food and accommodation are not as good as at Portage.

Bob begins flying twin-engine Cessna Crane’s and “.. a new type of Cessna..” (USAAC Cessna1a’s). The station also trains its pilots on the American Harvard. He prepares his parents for the possibility of his failing to qualify as a pilot (“washing out”). But on October 23rd he earns his Pilot Officer’s badge (with ribbon and star) along with the comment that he is “… just an average pilot who has progressed satisfactorily with training.” He was “… not recommended for flying by instrument [night flying]…”, and placed 37th in his class of 48. By the time he gets to England he will be judged more harshly still.

His letters continue to be full of anecdote and personal exploits. He purchases a new watch (Rolex Skyrocket), one of only 400 imported into Canada from Switzerland. He pays $40 (plus a trade-in) for it, approximately two-thirds of his monthly pay, in part because it has a “second sweep” (measures seconds as well as minutes and hours) that he needs for navigation. He refers in passing to a friend “Ollie” whom he describes as a “… frequent drunkard..” that apparently triggers another letter from mother warning him not to become corrupted. (July, 1942) In September he closes a letter to her with the words “Good-bye for now. No more harsh words from either of us.” It appears that Bob is determined to choose his own friends and his own way of living.

For the first time Bob makes passing reference to several airborne accidents in training that result in the deaths of mates, including one that he has witnessed himself. As well are comments regarding books that he has been reading (This Above All, Victory Through Air Power) and movies he has seen. Since enlistment he has viewed Moon Over Burma, Citizen Kane, The Fleet’s In, Sullivan’s Travels, Mrs. Miniver and Flying Down to Rio.

Also new are his frequent apologies for not having written sooner, a phrase that begins most letters sent from England in 1943.

Before leaving Dauphin is reference to Ruth Heney’s birthday present that he has instructed his mother to buy for the 18th of October. He implies that he continues to be in regular contact with Ruth by mail.

Embarkation Leave (October 23 – November 6, 1942)

That there are no letters extant suggests that he has spent his two-week leave in Toronto, a stop made between Dauphin and Halifax.

November 1942. Halifax

In his first letter from Halifax Bob rejoices that he has met up with Forbes Gilbertson, a fellow pilot and VictoriaCollege student.

“Forbes is here! Isn’t that wonderful? We are celebrating the re-union in the only fitting style. Did you know he is officially engaged? To Jane (Janice?) Elmore at that – and very happy about it. I’m beginning to wonder whether or not I did the right thing going no further than I did. Under the circumstances, though Forbes’ case is much the same, probably the answer is yes, but now I’m not so sure. Incidentally, all this talk about Ruth being ‘pretty discouraged’ applies to me too. I wrote on the 11th [a week earlier] and haven’t had a word in reply.”

(16.11.42)

That Bob failed to propose marriage (if he ever intended) is suggested, and now feels some regret not having done so. Though letters are exchanged regularly from England throughout 1943, 21-year old Bob and 18-year old Ruthie will never see each other again.

While in Halifax Bob visits his Aunt Kit and Uncle Bert Mackay, and cousins Andy, Janet, Mary and Elizabeth, “… like someone else I could mention, she really believes in lipstick and lots of it.”

England, 1943

Bob cables from England upon his arrival at PRC (Pilot’s Reception Centre) in Bournemouth. He and Forbes play tourist for the first three weeks of December, and Bob visits Budleigh Salterton for the first time. He is on hand for the beginning of Group 6, Goose Squadron #408, the second RCAF squadron in England stationed in Lindholm, Yorkshire. By August of 1943 they will move to Ouse-on-Linton and fly Lancaster bombers on night-time bombing raids into Germany. Bob moves from one station to another (Tatenhall, Saltehill , Dishforth, among others) in March of 1943, but cannot name them in letters home. He attends AFU’s (Advanced Flying Units) as well as specialty training courses of one or two weeks’ duration. He learns BEAM flying, night-time flying by compass and instruments. After a seven-week course at Dishforth OTU (Operational Training Unit), he is commended by his British instructor with “… a good average pilot. Had trouble at first as he did not know aircraft [Wellington “Wimpy”], but since we have pointed out his stupidity, he has shown very great improvement…Keeps his crew together quite well, and is a man of excellent principles. Recommended for a commission.” (22.06.43)

His letters home are full of his enthusiasm for the English people and for the country itself. During 1943 he visits London, Salisbury (the cathedral and close which he describes as “..right out of a painting by Constable…”, York (Yorkminster), Hathern (Smith family graves), Sadler’s Wells to see a ballet, Birmingham (reminiscent of Toronto) and, of course, Budleigh Salterton.

Budleigh Salterton

Bob arrives in Bournemouth in late November/early December, and waits for at least two weeks at the PRC (Pilots’ Reception Centre), while residing at the YMCA. An organization initiated by

Lady Francis Ryder places Dominion airmen with volunteer families as a place to call home while on leave. Through some administrative mix-up, Bob is not placed with Mrs. Henderson in Dawlish, as was first indicated, but with a Mrs. Constance Fairbairn in Budleigh Salterton, Devon.

He spends most of his leaves over the next year at 1 Copplestone Road. Here he meets airmen from Australia, New Zealand and Canada, and forms friendships with a couple of Aussies. He describes his first meeting with Mrs. Fairbairn: “ Mrs. Fairbairn met me at the [railway] station, which is only a short walk from her home. She is a kindly, elderly widow with one son serving in North Africa and another reported missing in the East Indies. Number one Copplestone is rather old and quite English.” His first meal is accompanied by a bottle of English ale, which … “I had exchanged for some lemon squash.”

Mrs. Fairbairn herself is described as a kindly, generous woman, and a habitual walker. She has a housekeeper named Nellie and a dog named Susan. She is well-travelled, having returned from India and Africa just before the outbreak of war, and tells of her experiences skiing and mountain-climbing in Switzerland. She has a 90-year old mother living in Bournemouth.

Copplestone Road is indeed his home away from home, and Mrs. Fairbairn his second mother. When Bob fails to return from the February ’44 raid over Augsburg, she writes several letters to the authorities in attempts to garner information. She corresponds with the Smiths in Toronto to keep up their spirits and pass on information.

In a 18.06.44 letter from Budleigh he becomes quite animated about one of his walks along the cliffs.

“Mrs. Fairbairn and I have gone on some pleasant walks together, mostly inland or along the tidal river. Last night we saw all manner of little birds, gulls and ducks by the score, and several pairs of swans. Those last I love

to watch, and hear, in flight – and a swan landing is truly a beautiful sight. Judgement and control personified. Along the cliffs where I usually go alone with the dog, the gulls furnish the entertainment. It is amazing how many tricks of flight can be noticed if you know what to look for. Stalls, glide approaches, power approaches, over-shoots, banks, slips, dives and pull-outs, use of flaps (I’ve decided that a gull’s feet are webbed in order to lower their stalling, and consequently their landing speed, just as much as to enable them to swim) and so on. Gulls have given me a post-war glider conscience, incidentally.”

Bob and his Mother

Throughout the correspondence with his family over a period of some thirty months, Bob occasionally addresses letters directly to his mother. There are regular references to Bob’s alcohol consumption, with an underlying tension not difficult to detect. When Bob first enlists he identifies his religious affiliation as “Baptist”, though he attends mass while stationed at Mont Joli, and regular church parades in England that may have been C. of E. in nature. He refers to “our church” in Budleigh Salterton as having been severely damaged by bombs. Close inspection of a map of the town indicates that the church closest to Copplestone Road is Baptist.

He assures his mother regularly of his abstemious habits, and indicates that his strongest drink in Canada is Coca-cola. He sells or barters any cigarettes he has.

Once in England, however, letters indicate a “loosening” of attitudes towards alcohol, perhaps to his mother’s dismay.

On 03.12.42 he has dinner with friends in a local [Bournemouth] hotel, and assures his mother that they drank “only cider”. On 20.01.43 he assures her,

“We won’t go into the present state of my morals, mother dear, for, really they haven’t changed. If anything I have more reason for sticking to the straight and narrow now that then [?]. There is a new and wonderfully assuring feeling inside of me that comes with knowing that someone worth waiting for waits for me.”

Eventually he decides to respond firmly to unsaid worries. On 5.03.43 he writes,

“… a soda fountain at home is a pub here. Similarly, a coke there is a beer on this side…English beer is almost as foul-tasting as Canadian, so you can imagine how I go for it. Naturally I can’t spend part of an evening in a pub with friends and not touch a drop. Beer, wine and hard stuff are in good taste in any company in England, and rightly so, I think. Therefore, if in future I refer to a ‘social glass’, it’s just that.

By the way, while on the general subject [of stimulants, morality?] my last compaign to train myself to smoke and like it ended in miserable failure towards the end of 1942.”

Operations

He completes several courses at various stations throughout England, after training sessions on Wimpy’s (Wellington bombers), Halifaxes and Lancaster bombers. He begins “crewing up in a very frank and open manner” in March, and practice flights are made with the same crew to become a single unit. A crew of five to seven includes a Pilot (Bob), Navigator (Cy Ridgers of Hamilton, called “Fully Operational” because of his moustache), Bomb Aimer (“Red” Beer of Nova Scotia), Air Gunners (Ronny Pettitt of Winnipeg) and Wireless Operator (Don “Ginger” Bowler of Leicester). Eventually Ronny Pettitt will be replaced by Air Gunners Clarence Draper and Douglas Mullock of Alberta, and Flight Engineer Fred Crofts of Scotland.

Bob describes Cy as his favourite of the crew, and Cy, “Red” Beer and “Ginger” Bowler are described as “… shy, quiet and likeable..” It is likely that the crew feels the same about their pilot, as he seems to be someone who makes friends easily. “The crews are becoming very close knit – ours, I think in particular. Eating, sleeping, flying together – it’s no wonder. Each day I become more attached [to] and proud of the fellows I chose….We’re none of us going to let the others down.” (06.07.43)

At the commencement of operations in May/June, Bob reports that “Ginger” is in favour of a posting “… in the Middle East, along with the rest of us.” He also has become innured to the deaths of aircrew, and mentions them in his letters (“Dewey Hall copped it the other day”; “..so-and-so went missing over Hanover, and one in the Middle East..”) Also mentioned are the un-delivered letters, an oblique reference to mail – and men – lost at sea or in the air. These comments might have been self-censored at one point in his training, but his growing maturity will not let him do so any more.

Letters home decrease in frequency once he is flying “ops”, which usually occurs every other day. No operations are conducted for the week of a full moon. He is involved with raids over Berlin, Hamburg, Stuttgart, Leipzig, Magdeburg, Schweinfurt and Augsburg, beginning on July 24th of 1943. By October he reports that his pay has increased to approximately $185 per month. On January 21st he is forced to land at Newmarket Racetrack on return from bombing ops over Magdeburg.

After one night raid over Berlin he reports that the Perspex of his cabin has been penetrated by a piece of flak, though he is unhurt, and he returns to base with a souvenir. Within a day this is reported in the Toronto Star, with the comment from his father – an experienced newspaperman – that “… he is a fine hand at writing a letter and not saying anything.”

By early February of 1944 he has completed 25 ops, and been saddled with additional duties as a deputy flight commander – paperwork that he did not enjoy. Near the end of the month he was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross. The next day he went missing, and was never seen again by his family.

The Letters

Attempting to paint a picture of Bob with his letters only is not unlike listening to one-half of a telephone conversation. It is further complicated by Bob’s restraint in recounting his exploits in England, and the sure knowledge that details of his life as a pilot would be censored by the military before even reaching Canada. Several of his letters bear evidence of excised material.

What is clear is that he loved flying and probably enjoyed his select status as a pilot. He adored the English countryside, Mrs. Fairbairn and the peace and quiet of Budleigh Salterton. I would like to have known him. His introspection in the midst of war was remarkable; what would he have thought about television, ballpoint pens, modern music or modern air travel?

Military training should take some credit for his maturity, a sense of responsibility far outstripping his youth. That he was part of a whole generation that grew up quickly, and sacrificed so much, is incontestable, and it is for this that we remember Bob.

By Simon Jensen

HIGH FLIGHT

O, I have slipped the surly bonds of earth

And danced on laughter-silvered wings.

Sunward I’ve climbed and joined the tumbling mirth

Of sun-split clouds – and done a hundred things

You have not dreamed of – wheeled and soared and swung

High in the sunlit silence. Hovering there

I’ve chased the shouting wind along and flung

My eager craft through footless halls of air.

Up, up the long delirious, burning blue

I’ve topped the windswept heights with easy grace

Where never lark, or even eagle, flew.

And, while with silent, lifting mind I’ve trod

The high untrespassed sanctity of space.

Put out my hand and touched the face of God.

John Gillespie Magee, September, 1941.

This is an incredible insight into a young mans life. I live down the street from him and attended U of T, as did he. I will visit his grave in the fall of 2022. Thank you for helping us Remember.

The Ridgers Family:

Many thanks for the correction in identifying the photo. I appreciate your comment, and for having taken the time to read this tribute. Whenever I think of those young men so long ago, I am constantly humbled by their dedication and sacrifice. We have much for which to be thankful.

Simon Jensen

Cobourg, Ontario, Canada

please be advised that the photograph to the left of Bob Smith is PO Cyril Ridgers not Fred Crofts of the same crew. They called him Freddy for short. This might be the reason for the error. Thank you, the Ridgers family.