The Bochum Raid

Certain periods in our lives were experienced with such intensity that they remain deeply etched in memory. The short time that Emmy and I were at Linton-on-Ouse was such a time. There was only the present, and it was full of excitement fear and for me, glory.

David Sokoloff February 1996

On November 4 1944 at 5.30 pm , a four-engine Halifax heavy bomber of 408 Squadron Royal Canadian Air Force, took off from its base at Linton-on Ouse in Yorkshire in the north of England. It’s mission was to bomb an oil refinery at  Bochum in the Ruhr valley industrial area of Germany a few miles east of Essen.

Bochum in the Ruhr valley industrial area of Germany a few miles east of Essen.

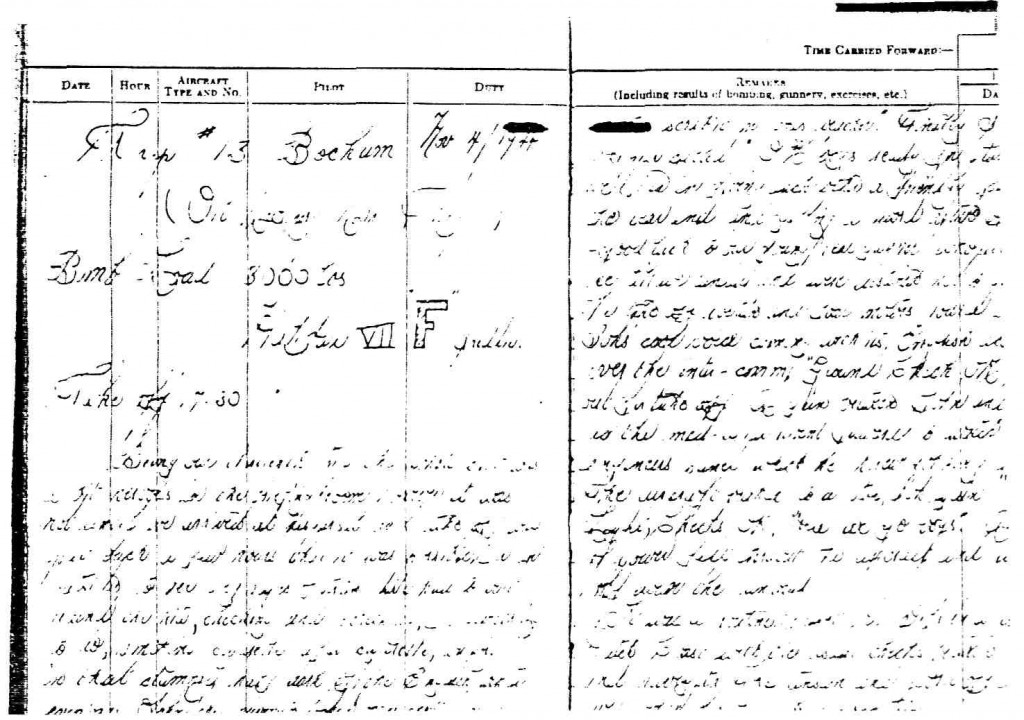

Alan Stables, our nineteen year old bombardier, wrote a report of the raid in his log book after he returned. He came across the account fifty one years later and sent it to Emmy and me. While we were on flying “operations” Emmy and I were living off base with our year old daughter Mitzi. Using Alan’s memoir we have filled in some background to give a more complete picture of what it was like during what was a momentous experience for us so long ago.

Home base of 408 the Goose Squadron RCAF was located in the north of England, ten miles northwest of the city of York at Linton-on-Ouse. Linton housed two squadrons, 408 the “Goose” Squadron, and 426 the “Thunderbird” Squadron. Linton was one of seven operational and four training airbases which made up 6 Group, which was a predominately Canadian The RCAF provided the pilots, navigators, bombardiers, and gunners, all the crew that is, except the flight engineers who were provided by the RAF Group headquarters were at Allerton Park Castle, a 75 room Victorian mansion near Knaresborough Initially at Linton the aircrews flew Wellingtons but later converted to Lancasters and Halifaxes. During the war 6 Group lost more than 1500 bombers not including those that crashed in England. Each crew was made up of seven men so well over 10,000 failed to return from operations. The two squadrons at Linton lost 321 bombers.

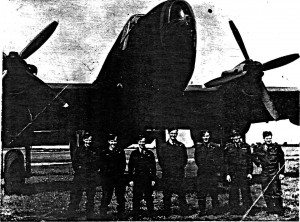

There were seven of us in the crew, I was the pilot; I was twenty four years old and had been at Yale University studying Architecture and had joined the RCAF in Montreal. John Sargent, our twenty three year old navigator was an accountant who lived in New Hazelton way up in northern British Columbia. John was a mystic. I think he was part Indian. After the war he owned the store and the movie theater in their small town where he and his sons taught wilderness survival techniques to oil exploration personnel

There were seven of us in the crew, I was the pilot; I was twenty four years old and had been at Yale University studying Architecture and had joined the RCAF in Montreal. John Sargent, our twenty three year old navigator was an accountant who lived in New Hazelton way up in northern British Columbia. John was a mystic. I think he was part Indian. After the war he owned the store and the movie theater in their small town where he and his sons taught wilderness survival techniques to oil exploration personnel

Dave Hardy, our rear gunner, was nineteen years old and came from from Saskatoon Saskatchewan. Like his father before him in the first world war, he became a prisoner of war. 1 did not know him well, Alan kept him in line. Hex Hexemer was our ground crew chief. He came from Toromto. He was thirty nine years old. He took care of cur aircraft as though we were his own kids.

daylight, and one to Kiel at night

When we ourselves became an experienced crew, we took new pilots on a “familiarization” trips. They were amazed at how the crew would respond to orders before they were given This was because we flew at night and were, in a sense, flying alone, if we were at the right height, at the right place, at the right time, we would be in the comparative safety of the main bomber stream. We only knew for certain that we were not alone when we saw the loom of another aircraft, or the glow of someone’s exhausts, or when a flash lit up the sky. Since mid-air collisions were not uncommon and keeping a good look-out for fighters was critical, we were very dependent on each other for survival and we became closely “tuned”to each other.

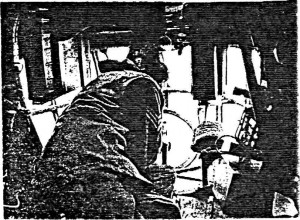

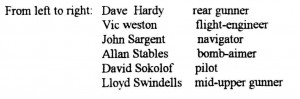

Our aircraft “F” for Freddie was a Handley-Page Halifax Mark VI1 heavy bomber powered by four 1680 horse-power Bristol “Hercules” sleeve-valve radial engines. The plane’s loaded weight was 65000 pounds maximum. The fuel capacity was 2196 gallons of gasoline. The plane could carry a 14000 pound bomb load. The maximum range was 1800 miles with a service ceiling of 20000 feet. Cruising speed loaded was 170 miles an hour. Maximum speed was 280 miles per hour.

Alan, the bombardier, with his bombsight,was up in the nose. Behind him sat John Sargent the navigator. John had a small window on which was painted a vase with flowers to make things more homelike. John and Alan shared the operation of the two major radar navigation systems, Gee and H2S Gee allowed fixes to be taken by “strobing” onto a cathode screen.the elliptical radar signals being broadcast from England. Gee was very accurate but had a limited range and was subject to jamming.It became less and less effective the deeper we penetrated enemy territory. H2S was a blind map-reading scanner. Unfortunately the scans were often difficult to interpret since the equipment was somewhat primitive.

Behind the navigator sat Scotty the wireless operator. Scotty’s ceiling was the my floor Scotty’s job was an unenviable one He had to monitor the quarter-hourly broadcasts from Bomber Command,and in between broadcasts he had to listen in case anything else was transmitted which might affect us. In the target area Master-Bombers would direct the main stream, they would tell us for example to bomb upwind of the yellow target indicators Scotty had to sit in his tiny dark box just listening under circumstances requiring iron nerves.

Behind me was Dick Richardson’s flight-engineer’s station with the fuel and engine gauges and controls. Dick helped me during take-off and landing as we did not have power assists and it took two of us to manage the “thirty-ton truck” Dick was happy that we were assigned the Halifax Vlls which were equipped with radial engines; he didn’t like the in-line glycol cooled engines on the Halifax 1 l’s which we flew during final Heavy Conversion training.

Although the Halifaxes suffered heavier losses than the Lancasters due to the their 2000 foot height ceiling disadvantage, the survival rate among Halifax crews who were shot down was higher than that of the crews flying Lancasters. This was due to the design of the Halifax which had well placed escape hatches. The wireless operator and the navigator were located in the nose of the aircraft close to the forward escape hatch instead of in the mid-section of the fuselage as in the Lancaster.

The following is a transcript of Allan Stables’ log :

Being our thirteenth trip, the whole crew was a bit nervous Superstition was usual among air crews. In our crew, Sok our skipper, had to bring his battered everyday uniform cap. One crew suffered because their good luck charm was their skipper’s white sweater which could not be washed or cleaned without risking losing its protection.

Once all the complete crews were present at the briefing room, the briefing officer spelled out the target, the route, the take off time , the speeds and altitudes, the points where we had to change course and or height, available emergency airfields, the composition of the raid and its purpose, which was the destruction of an oil refinery outside the city of Bochum. Then the meteorological officer gave us the weather forecast for the trip and it didn’t look good. We were to climb through the heavy overcast, climbing up through holes in the clouds as heavy icing was expected.

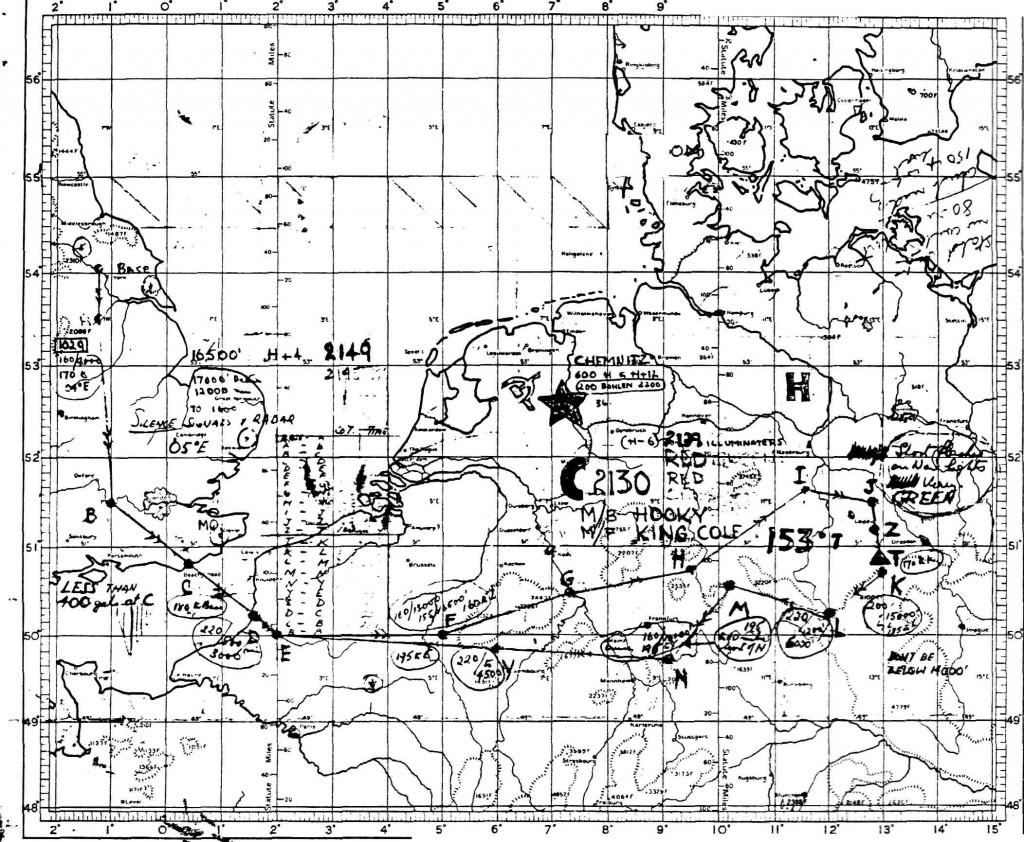

On a raid to Chemnitz, southeast of Leipzig,. We took off in icy conditions. Our squadron lost three out of fourteen Halifaxes shortly after take-off due to heavy icing. One of the bombers crashed in York killing six of the seven man crew. The seventh was the wireless-operator who baled out too low for his parachute to open fully. When the plane hit the ground and exploded, the blast blew him up into the air opening his parachute. He was injured but was the only one who survived. Below is my “Captain’s of aircraft map” of the Chemnitz raid on which we were airborne 9 hours 15 minutes.

CAPTAINS Of AIRCRAFT MAP NEWCASTLE to PRAGUE

Take- off was scheduled for 4:00 PM. Once a raid was announced the navigators and bombardiers had to go to the briefing shack at least a half an hour before the rest of the crew to prepare their flight plans.

The raid was to consist of 400 Lancaster and Halifax heavy bombers carrying a mixed load of heavy case high explosive bombs and incendiaries. We were scheduled to be airborne for six hours. “Mosquito” were to mark the target with green and red target indicators. De Haviland” Mosquitos” had twin Rolls-Royce engines and carried a pilot and a wireless-operator/navigator. They were used by the Master Bombers as part of the Pathfinder Force to mark the target.

John, our navigator, looked occasionally up at the overcast sky saying “Why the hell don’t the bastards scrub it in this weather?” The Catholic Chaplain came around to give us comfort. Finally the skipper called “It’s okay boys, ready for starting.” We climbed in through the rear escape hatch giving each other a friendly pat on the rear and getting in a word or two of encouragement and good luck to our tail gunner who we normally wouldn’t see again until we landed.

We settled into take-off positions, lying down in the crash position behind the main spar as one by one our engines roared into life. Sok’s cool voice with its English accent over the intercom ran through his take-off checks “Hydraulics trim mixture pitch fuel flaps gyros, etc. Then he and Dick Richardson ran the engines up the to full power to check the magnetos and the instruments.

Once we were airborne we went to our “battle” positions listening to the interchange between the pilot and the engineer… “lock throttles – adjust the pitch on the starboard outer – wheels up and locked Skipper synchronizing engines – adjusting trim tabs – throttle back to climbing boost” . Sok said “Every one check back when in position.”. Then we all called back starting with me then John, then Scotty, then Lloyd the mid-upper gunner, and last Dave Hardy the rear gunner.

Sok said “Okay John give me a course”. We climbed up through the scattered clouds into the eastern darkness with the fading light behind us, leveling out at seven hundred feet. We would hold this heading and altitude over the North Sea until we were within forty miles of the Dutch coast in order to avoid enemy radar. Then would have to climb like hell to be at fourteen thousand feet above the range of light flak as we crossed the enemy coast.

We had settled in but as usual I was concerned about my sandwiches, chocolate bar, and apple. If thev were located too close to the exhaust heaters they would melt and if they were too far them would freeze solid since at final altitude it would probably be about seventy degrees below zero Fahrenheit — unfortunately the distance between too close and too far was only about six inches. An enormous amount of creative effort and energy was devoted to this problem by our ground crew.

It was a routine flight to the Dutch coast with the checks continuing between the pilot and the navigator and the tension wore off. Now the gunners had to search the sky for night-fighters. If they saw them first we had a pretty good chance of getting away. From the nose position I tried to watch below and slightly behind, This was our blind spot where we were most vulnerable to enemy night-fighters equipped with upward-firing twenty millimeter cannon.

Coming up to the Dutch coast we could see flashes of light flak and the beautiful trace it makes streaming upwards as if fired from a hose. It was dark now and every now and again we would see the loom of one of our own aircraft which was comforting because it meant we were part of the bomber stream

At this point we started climbing . We began to have difficulty at about ten thousand feet and by fourteen thousand feet Dick suspected that we had carburetor icing . We had gone on oxygen at twelve thousand feet and we had to climb to nineteen thousand which was our height to bomb The aircraft at the head of the bomber stream were at the lowest level with those following stacked up increasing heights so as to lessen the danger of running into someone else’s bombs. Sok came over the intercom ordering me to jettison some of the bombs as the aircraft just wouldn’t climb. I went back and jettisoned half the load but the best we could make was an extra 1000 feet. We were five thousand feet below

everyone else, a very dangerous position to be in and we had at least another hour and a half to go to the target. Scotty went back to shovel out the Window*. Then he returned to his radio to receive the quarter-hourly broadcast

from bomber command Then he backtuned his transmitter to German fighter vector-control frequency and broadcast static at full volume from a microphone next to our generator.

•Window was introduced in July 1943. It consisted of 9 inch strips of aluminum foil which showed up on the German radar screens rendering them virtually useless . The German response was to use various forms of illumination available at the target area to make the bombers visible to the night-fighters. Window was still useful in disguising the size of the incoming force and in blinding the radar controlled Flak guns.

Ahead the searchlights, hundreds of them came to life, pointing accusing fingers against the black sky. I wondered how the hell we would get through them at this altitude without being “coned”, but I didn’t have much time to wonder as the rear gunner yelled “fighter port go”. Down we went to the left in a “corkscrew.” This was our evasive action, but very shortly the rear gunner called to resume course telling us that a Messerschmidt 210 had made a pass at us.

“Ready for run-up to the target” — “Christ” I yelled as a fighter came head on at us. The trace of his cannon seemed to be coming right at me . I closed my eyes and said a prayer. The engineer yelled “Port engine on fire Skip, let’s get the hell out.” The cannon shells of the fighter had hit our port inner engine and as I looked out I could see the flames licking back over the wing in which our gas tanks were stored. Sok’s voice came cool over the intercom “Feathering

port inner, hit the graviner* switches Dick, prepare to abandon aircraft, bomb doors open, drop your bombs bomb-aimer”

*The graviner switches controlled compressed incombustible carbon-dioxide which could be sprayed into the engines and hopefully serving as engine fire extinguishers.

/ looked out, my bombsight was on the target area now burning and smoking from the earlier bombs. . The bomb doors were open and I pressed the release tit feeling the bump as the bombs left the aircraft. Then the searchlights coned us and flak started coming up. What happened then was that as 1 was dropping the bombs the crew left their stations and went to the exits. Sok stayed at the controls but didn’t open his escape hatch but put the plane into a steep dive

to put out the fire. I was in the nose trying to untangle my intercom cord from my parachute wondering if I would ever get them apart. I was about to give up when John signaled to me. He yelled into my ear, “Hang onto me and we’ll go together.” John knew as well as I did that this was crazy.

Finally we were down to four thousand feet and out of the searchlights. Sok called the gunners but got no reply. “Bomb-aimer please check the crew. Navigator give me a course.” The dive had put out the fire. I went back to the rear to see if Dave Hardy was hurt. I found the Baron by the rear escape hatch holding his head but not plugged in. “What the hell are you doing?” I yelled in his ear. “We’re OK, get back in the goddamn rear turret” “OK, Al, thanks” “What for you nut” I replied. Then I tried to get into the turret, but had to report to Sok that it was impossible.

The Baron wanted to talk but I was off to the rear turret which was jammed sideways and Dave Hardy was gone. This was serious because it meant that now we were defenseless against stern attacks.

Rear gunners baled out by rotating the turret and dropping out backwards. Unfortunately Dave Hardy had pulled out his intercom plug and hadn’t heard that we had got the fire out and when he baled out he jammed the rear gun turret sideways.

. We could see the searchlights coning a couple of kites. There was no flak, but fighters came in and in a few seconds two more bombers went down in flames In the hurry and excitement as we opened the escape hatches in order to bale out, the navigator’s log and maps had been sucked out of the aircraft Now John had to take us home by “dead reckoning” and guesswork. Our main fuse panel had been hit. We had no radar, no fuel gauges, and we didn’t know whether we had lost fuel.

Then the mid-upper gunner reported two fighters tailing us. One came in and we corkscrewed* to starboard. During the next hour and we were attacked seven times. We tried taking shelter in what little cloud there was. A couple of times when we came out of it a fighter flare would drop and in would come a fighter. We were now down to two thousand feet. We lost him and kept heading west while John was trying to figure where we were.

* The “Corkscrew was standard evasive action from fighter attack. If the attack was from the left and below you headed into the attack with a dive to the left followed by a climbing roll up to the right. Since the fighter pilot had to aim ahead of the target he was forced to aim blind.

With no fuel gauges and at our last reading our fuel registering low, Dick said that we should try to land as soon as we were beyond enemy held territory. John said that we should make for Brussels which he thought was about fifty miles to our north. As we headed towards the city we could see the air-field runway flares lit up. We had already been forced so low by taking evasive action that we were probably down below 300 feet during the last ten minutes of our approach. We did not identify ourselves or turn on our lights as we didn’t want to expose our position to any fighters which might have been lurking. They would follow the bomber stream on the way back picking off stragglers.

Once when returning from a raid we were stacked up waiting our turn to make our final approach when Lloyd yelled “Jesus there’s a plane next to us with black crosses on its side!” It was a Junkers 88. They were “Intruders”. They would strafe aircraft as they were about to land.

(We were equipped with tanks of compressed nitrogen which, filled up the gas tanks as thy emptied with a non-combustible mixture. This was unreliable even when no damage had been sustained.) Fire engines and ambulances came screaming across the field. A truck stopped and picked us up and we were taken to an office in the control tower. After a short while we were taken by truck into Brussels to the Imperial Hotel a place with everything including a show lounge with live entertainment! We got the driver to stop at a bar on the way where we traded a parachute for some brandy. When we got to the hotel room it was difficult to sleep, we were so keyed up. We drank brandy and lay awake for hours going over what had happened

The next morning a truck took us back to the airport which was a shambles. It had been taken by the Allies only three days before. There were piles of bombs alongside the runway and there were damaged aircraft, both German and Allied all over the place.

We went out to our plane to collect parachutes and souvenirs. It was half full of dirt and we counted over a hundred bullet and flak holes. Sok couldn’t find his sheepskin-lined leather jacket. The civilian armed guard thought that we were accusing him of stealing it. There was a big argument but. we found it in the plane. We were all impressed because we didn’t know that Sok spoke French.

We hung around till a snotty transportation officer told us we would probably have to wait at least all day and maybe longer before we could get a ride back to England. Sok told the officer that we’d be happy to stay in Brussels for

as long as possible which made him change his mind and he got us onto a DC. 3 “Dakota” transport that was taking some air crew and some escaped prisoners back to England.

Scotty Frazier Moe Blad Allan Stables John

Sargent David Sokolof, Dick Richardson, Lloyd Swindells,

Hex Hexemer

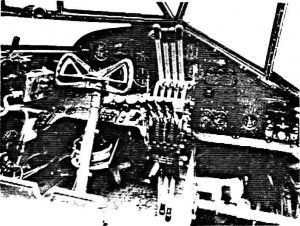

John and Cathy’s wedding

After we finished our tour John Sargent married Cathy, a Canadian nurse. The crew were at the wedding and I was best man. We’ve kept in touch with Cathy. We visited Kay Scotty’s widow in Salmon Arms Manitoba a few years ago , but we have lost touch with Lloyd’s wife Jeanne.

.Allan and Evelyn live in White Rock BC just over the border We stay in touch and we spend time together every year. This memoir is for all our children and grandchildren.

After landmg from our last operation.

This is an amazing story of the hero’s that fought for our Country!! Thank you for writing and sharing. Uncle John was a great man, Dianne Boutilier (Cathy Sargent’s Niece)